Building hull and deck

Latest updated Wednesday, November 23, 2016, 65 comments

sheer strip | keel strip | planking | gluing | outer stems | sanding | epoxy first coat | fiberglass | second coat | third coat | lift the hull

Installing the sheer strip

If you do not have full length strips, the sheer strips must be scarfed before installing. A simple way is to glue a short scarf piece (5-6 cm - long enough to hold the strips lined up, but short enough to allow smooth bending) on the inside over the joint. If your woodworking pride does not permit such a simple scarfing method, you can use a beveled scarf at least 6 cm long.

Install the sheer strip with the lower edge against the sheerline marks on the molds and stems (if you are using bead-and-cove strips place the first strip with cove side up). Use 14 mm staples into the molds. Have a good look at the gentle curve and adjust if you see any humps or hollows. Note that the sheer curve normally accelerates slightly towards the stems. Disregard the odd sheer mark on the molds if needed - a beautiful curve is the important goal here. Use the spirit level to get both sides exactly on the same height. When you are satisfied, glue the strip to the stems and trim it to length.

On canoes with a severe bend towards the stems, it is a better idea not to force the sheer strip all the way up in the stems. Let the strips follow their own gentle curve instead, and build up the stems with short piece afterwards. Take care to get the sides symmetrical.

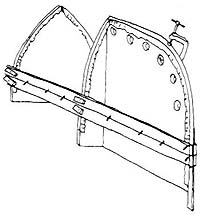

In hard chine hulls it is often best to install chine strips from the start as well. These are positioned to bisect the chine angle and are stapled on to the cut off corner of the mold. With chine strips it is easier to control the position of the chines towards the stems.

Install the keel strip

Install the keel strip the same way - stapled to the molds and glued to a short cutout in the inner stem. Long stems will have to be let into mold 1 and 12. Use a plane to blend the keel strip seamlessly into the stems.

Install the keel strip the same way - stapled to the molds and glued to a short cutout in the inner stem. Long stems will have to be let into mold 1 and 12. Use a plane to blend the keel strip seamlessly into the stems.

Planking

Now the fun begins. Everything you have done up to this point have been preparation for this. The planking transforms the materials into a boat.

Square cut strips: do not glue anything until the entire hull is planked (maybe a little glue at the stems if the staples doesn´t hold them tightly).

Bead-and-cove strips: glue each strip with carpenters glue as you go. Take care to fit the planks tightly together since nothing can be corrected when the glue has set.

Attach the planks one at a time, starting in the middle, holding the strips together tightly with the hand and shooting a staple in every mold. I use one row of staples between the molds as well, bridging the planks. Progress symmetrically on both sides, two planks at a time.

Some go to great length to avoid the staples. Fully possible, but it takes time since you can only glue one strip at the time. Use tape, rope, elastic chord or clamps to hold the planks until the glue sets. Normally a hull is planked in a couple of hours (square cut strips) or slightly more (bead-and-cove). Stapleless construction increases this by a factor four or five. Is it worth it? Maybe, but think about it.

To staple into the stems an iron dolly is needed to avoid deflecting the stem. Hold a heavy hammer or axe, vice, large clamp or similar behind when stapling.

Scarf the planks as you go. Start from on end and install the plank as long as it reaches, then a new plank from the other end and where they meet, hold them together and cut through both with a thin bladed (Japan style) saw. Shoot a staple bridging the joint - if needed a staple into the adjacent plank. I find it easier to keep the joint fair, if the scarfing is done between molds. Make sure no scarfs end up close to each other - at least two planks between. Distribute the scarfs evenly along the hull - forward, aft, middle. Put your staples in neat rows, like rivets in a clinker dinghy – looks better if you finish your kayak bright.

Sometimes the holding power of the staples is inadequate in particle board. Then use a 1" thin nail, preferably through a piece of cardboard, to make it easy to remove without damaging the wood.

On the bottom, the strips will have to be bent sideways as well, inducing the risk of strips lifting from the molds or between the molds. Check this repeatedly. A raised strip will form a hump that will be sanded hard later, at the risk of reducing the thickness to almost nothing. Not a catastrophe - you can always glue a new piece of strip inside and sand it all even, but it is a lot of unnecessary work.

Very wide canoes may impose planking problems. At the stem-keel transition two or three strips will have to be severely twisted to fit. Do not fight them. Let them follow their own curve and fit a filler wedge afterwards instead. After a couple of problematic strips things will ease up. Extremely short and wide canoes may be better planked from sheer to chine and then from keel and out.

Very wide canoes may impose planking problems. At the stem-keel transition two or three strips will have to be severely twisted to fit. Do not fight them. Let them follow their own curve and fit a filler wedge afterwards instead. After a couple of problematic strips things will ease up. Extremely short and wide canoes may be better planked from sheer to chine and then from keel and out.

Using too wide strips (more then 20 mm) pose a special problem. They tend to bulge between molds. Such tendencies must be stopped immediately, otherwise the hull will be impossible to sand. Press back the bulge (overcompensating slightly) while you staple the next strip in position.

The last strips must be fitted both ends against the keel strip. My way is to attach the strip to all molds except the one closest to the strip end, hold the strip in the correct position above the keel strip and then let a thin bladed (japan) saw follow the keel strip. It usually fits nicely - at least after a couple of tries. Minute corrections can be made with a plane or sandpaper. Occasionally when no one is watching the old carpenters rule applies: "Cut to fit - beat into place". Too short? Well best is to start all over with a new strip, but the quick-and-dirty builder save some time by filling the gap with epoxy and sanding dust or press a piece of veneer into the gap. Functional? Yes, absolutely. Pretty? Perhaps not, but beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

When the hull is planked it is time to look it over carefully. If it is not glued, there is still time to correct any unevenness. A low plank can be tapped from below until correct. A high plank must be planed or sanded down after gluing. Take a step back and enjoy the result of your work. This far into the project even the most convinced skeptic start to believe that this eventually will become a kayak or canoe - and that is a fun project. In old times the last plank - the shutter plank - was an important step and was celebrated. Often it meant that invoice number two could be handed over to the customer. When you are done dreaming it is time to glue (if you use square cut strips).

Gluing

In a cold shop both the epoxy and the hull may be heated up (25-30°) before gluing - fx with a car heater under the hull.

Mix a little epoxy without any additives and distribute over the hull with a large stiff disposable brush, working it into the seams carefully.

Do not mix more then a decilitre at a time - with large volumes there is risk for an exothermic chain reaction, instantly curing the epoxy to a smoking hot lump of plastic. If you need larger batches, mix them on a shallow tray, where the cooling surface is larger.

Work the epoxy into the seems vigorously, without pressing so hard that you upset the strips. The brush may shed hairs like a dog in May or the epoxy may foam, but that does not matter. The epoxy seeps into the seams no matter how tight seams you have achieved - it is formulated to go in between the wooden cells, typically 1-2 thousands of a millimeter. On the other hand, your less-than-perfect seams may need a second filling with thickened epoxy.

Outer stems

Plane or sand the stems. Prepare material for outer stems. Best is a bendable hardwood like ash or cherry. Cut lamination strips according the the shape of the stem: 2-3 mm for canoe stems and kayaks with tight curves (3 laminations thick), 3-4 mm for torpedo shaped kayaks (2 laminations thick) or one straight piece 15x15 mm for straight stemmed kayaks.  Glue strips in position, fix with screws until the glue has cured. First brush unthickened epoxy on the endwood on the strips (to prevent epoxy from being sucked into the wood, leaving only filler in the joint) before spreading thickened epoxy on the stem and lamination pieces.

Glue strips in position, fix with screws until the glue has cured. First brush unthickened epoxy on the endwood on the strips (to prevent epoxy from being sucked into the wood, leaving only filler in the joint) before spreading thickened epoxy on the stem and lamination pieces.

When the glue has cured, remove the screws, plug the holes and plane and sand the stem. The order of the steps is critical - start by shaping the stem to a seamless extension of the planking. Then work on the profile - shape it to a nice and gentle curve blending in with the keel. Last, round the stem to approx 5 mm radius (a good compromise between looking sharp, low friction in the water and durability).

Fair and sand the hull

This is the second task that requires a little extra care and patience. When you are done, nobody can see how long it has taken - only if it is well done. First remove all nails, staples and/or screws. Staples are best removed with a staple remover (what a surprise!) - fx the Rapid. Grind back and sharpen the lower jaw slightly, so it is easier to get a grip on the staples. The advantages of the Rapid is that it grips the staples and pull them in one movement (digging with a screwdriver and pulling one staple leg at a time with a pair of pliers works - but who wants to triple the time spent pulling staples? It is bad enough even with proper tools). Epoxy from gluing protects the wooden surface, minimizing dents. Fill gaps and holes from staples and nails with a mix of sanding dust and epoxy.

Remove all surface epoxy, glue blobs and such. You can use a scraper or coarse sandpaper, but my favorite is a small angle grinder with a coarse (40-grit) fiber disc - quick but slightly risky - a seconds lack of attention and you may be through the hull  (practice on something disposable). You must not remove wood with the angle grinder - only epoxy (stop before you loose the shine of unsanded epoxy in the seams). Then I remove the circular marks from the disc with a band sander running along the grain only - still 40 grit and still no real sanding down in the wood.

(practice on something disposable). You must not remove wood with the angle grinder - only epoxy (stop before you loose the shine of unsanded epoxy in the seams). Then I remove the circular marks from the disc with a band sander running along the grain only - still 40 grit and still no real sanding down in the wood.

And now finally, the real sanding. And by the way - I prefer not to use a plane for this. Cabinet makers always claim that planed surface is prettier than a sanded - no dust dulling the structure. I agree in theory, but the irregular grain in the strips is hard to handle without ugly tear-outs. Start with 40 grit on a longboard. Doing it this way instead of using machines comes a few advantages:

- More control over the fairing process.

- You achieve fairness quicker.

- Less dust.

- Less noise.

- You exercise the same muscles you need for paddling later.

Sand along the fibers. Use a dust mask (imperative if the epoxy has cured less than a week or if you are using smelly wood like Cedar). The sanding in this step is not supposed to produce a smooth surface, but a fair hull. Machines have too small a sanding area to achieve this. Good light is important to see humps and hollows - preferably a hand lamp held low on the hull.

When no unsanded wood remains anywhere - you are probably done. In practice, you will have a number of small dents or hollows that realistically cannot be sanded away without losing planking thickness. Those will have to be filled with epoxy/sanding dust (I believe you will have a fair supply of such by now).

Next step is removing the scratches from the 40-paper with a quick round with 80-paper on the longboard, followed by 120-paper in the hand or on a random-orbit sander (5 minutes or so). Do not go finer than 120 in this step. With all sanding it is important to change paper as soon as it dulls. Using dull paper burnishes the surface and decreases epoxy penetration in the following steps. It also may heaten the epoxy from friction, producing a messy smear.

First epoxy coat

The reason for this first epoxy coat is to seal the wooden surface, so it allows the epoxy to stay in the cloth when laminating. It is therefore important that this first coat is done with as little epoxy as possible - all extra is an unnecessary and unwanted ballast. My way is to pour a small amount of epoxy on top of the bottom and quickly distribute it over the entire surface with a rubber squeegee (a white one, otherwise you may end up with a hull looking like someone tried to set it on fire). Press hard on the squeegee and work quickly. More than a deciliter for the hull is too much. When the epoxy has cured, sand lightly with 120-paper to remove any wood fibers that could catch the cloth.

This first coat is important to achieve a low weight in the finished hull. Without it you have to keep adding epoxy until the wood is saturated before the cloth is wetted out properly - which could a lot more epoxy than necessary.

Fiberglassing

Center the cloth over the hull (use 150-165 g/m2 twill weaved cloth, compatible with epoxy – to recalculate weights: 1 gram per square meter = .02949 ounces per square yard, 1 ounce per square yard = 33.91 grams per square meter). Remove wrinkles by working the cloth perimeter out towards the ends. Work slowly and carefully until all wrinkles are gone and the cloth adhere to the entire hull. On hulls with sharp vertical stems you need to cut the cloth at the stem, but on some kayaks with "nice" shapes there will be no cuts or darts. Cut the cloth a couple of inches below the sheer and save the offcut pieces.

Center the cloth over the hull (use 150-165 g/m2 twill weaved cloth, compatible with epoxy – to recalculate weights: 1 gram per square meter = .02949 ounces per square yard, 1 ounce per square yard = 33.91 grams per square meter). Remove wrinkles by working the cloth perimeter out towards the ends. Work slowly and carefully until all wrinkles are gone and the cloth adhere to the entire hull. On hulls with sharp vertical stems you need to cut the cloth at the stem, but on some kayaks with "nice" shapes there will be no cuts or darts. Cut the cloth a couple of inches below the sheer and save the offcut pieces.

Pour a small amount of epoxy on top of the bottom and spread it with the squeegee. Work towards the ends and down to the sheer. This first go with the squeegee lightly floating in the epoxy, without touching the cloth. After a couple of minutes, the glass becomes invisible as the epoxy wets out the fiber bundles and anchors the cloth firmly on the surface. Then you can work a little harder to spread the epoxy over a larger area. Work only towards the ends and down to the sheer - reversing the action may develop wrinkles, impossible to smooth out. Watch out for epoxy pooling, as this allow the cloth to float from the surface and later be sanded off - remove with the squeegee. Also, watch out for starving areas with still visible glass fibers - add more epoxy.

The squeegee is the best tool for working the air out from the fiberglass bundles and replacing it with epoxy. Each glass fiber "tread" contains approx 400 filaments (1/100 mm each) and the cloth is pretreated with a chemical sizing (usually Silan) that stabilizes the cloth structure during transport and handling, keeps moisture out but also traps air. It takes a steady pressure on the squeegee to force out all the air. Trapped air might later develop into blisters when the sun heats up the surface.

When the cloth is invisible - no white spots - you are done. This should be achieved with minimum epoxy. Excess may lead to runs and drips, pooling that floats the cloth from the wood, uneven surface and decreased strength. Ideally, the cloth is covered to 3/4 - wetted out but the weave structure visible. Shiny spots after 10-15 minutes indicate too much epoxy.

Do not raise the temperature during curing, as this may force air out from the wood, lifting the cloth. It is better to raise the temperature slightly before laminating, and then let it slowly cool off.

Second coat

The purpose of the second coat is to fill the weave and level the structure of the cloth. Do not try at this point to build resin thickness  – the likely result will be runs that have to be sanded later. Brush on the epoxy and smooth with the squeegee. When the epoxy has cured enough to be workable (6-8 hours depending on temperature), sand lightly with 120-paper and clean the hull with a moistened rag. Look closely at the surface. If it is even, with no sign of the weave structure you can go directly to the finishing epoxy coat. Otherwise, another intermediate coat is needed.

– the likely result will be runs that have to be sanded later. Brush on the epoxy and smooth with the squeegee. When the epoxy has cured enough to be workable (6-8 hours depending on temperature), sand lightly with 120-paper and clean the hull with a moistened rag. Look closely at the surface. If it is even, with no sign of the weave structure you can go directly to the finishing epoxy coat. Otherwise, another intermediate coat is needed.

Uneven surface?

Go lightly with the sanding if humps appear - that may indicate inadequate sanding prior to glassing or that the glass has floated up in excess epoxy. Aggressive sanding then cuts the fiberglass compromising the laminate strength. Use a sensible mix of sanding and filling until you are satisfied.

Note that epoxy duplicates the underlying structure faithfully. Just adding epoxy will never achieve fairness. It is the sanding that produces fairness.

Third coat

The purpose of the third coat is to bury the glass cloth so that the surface may be sanded smooth without hitting the cloth. The coat should be an even coat. I find a brush with cut bristles good for this. Work vigorously with the brush in different directions to ensure an even film. It is hard to judge film thickness by sight, but try to listen to the brush and feel the friction. A too thin coat leaves a flat finish with visible brush lines, too much and you get runs and curtains (do not try to spread these with the brush - use a scraper when the epoxy has set a couple of hours).

Lift the hull

Kayak: Tap the molds so they come loose from the hull. Lift slowly and carefully in the stems - do not jerk.

Canoe: Remove the molds in the ends and the stem mold from the strongback and lift the hull. Tap the molds loose and remove them.

Place the hull right side up on the strongback with some foam as protection.