Kayaks

Latest updated Sunday, November 22, 2020, 52 comments

finish the inside | cockpit| deck and cockpit | strip the deck | rim and flange | foot support | join the deck and hull | knee support | skeg

Finish the inside

The inside is treated in the same way as the outside – with a couple of exceptions. Use a contoured scraper instead of sandpaper for parts of the fairing. Skip some of the epoxy coatings – leaving a little weave structure eliminates much of fairing work and may serve a antislip surface in the cockpit.

Take care of the inside as soon as the outside is done. A pause in the project with a oneside laminate, often leads to a deformed hull, and troubles to match hull and deck. If necessary, leave the molds in place, until you continue.

In a kayak the finish is not as important on the inside as on the outside – except maybe in the cockpit area. But make sure it is smooth enough to avoid trapping air at joints.

The cloth is best draped athwartships, short pieces from sheer to sheer. I find it easier to handle the smaller pieces than a full length piece – reducing the risk of tension wrinkles and blisters. In the stems it is easiest to use small triangular pieces to fit at the sides of the stems and a narrow tape to cover the inner stems itself. Otherwise it is hard to avoid wrinkles and blisters.

Double the cloth in the cockpit where you step when entering or exiting the kayak, and where you have your heels when paddling. Be careful not to shift the cloth when working epoxy up against the sheer – it will then lift from the bottom and create large blister as soon as you turn your back to the hull. Some builders have had success with short haired paint rollers, but some have also had problems with orange peel structure (which may be corrected with rubber squeegee if done immediately). Some have tried to place the cloth in wet epoxy, smoothing it out with your hands. It may be hard to eliminate all wrinkles, but the cloth sticks to the epoxy and the risk of inadvertently shifting the cloth is minimal.

Wrinkles not possible to smooth out may be cut with a sharp knife (angular to the strips) and pressed down. If you must cut along the strips, I recommend that a new piece of cloth is laminated over the cut. Blisters and wrinkles that cannot be removed is best left as they are. When the epoxy has cured it is easy to cut them and if needed replace the cloth locally.

Be careful not to leave excess epoxy pooling in the bottom – an unnecessary ballast and one of the worst reasons for a heavy kayak. There is also an added risk of cloth floating up in the excess epoxy, losing contact with the wood and resulting in decreased strength.

Customize the cockpit

When you build the rim there is a good reason to adjust it to your anatomy. A homegrown kayak should be more comfortable than anything on the market (more info on the cockpit page).

Sit with your back against a wall. Note on the plans the height of the rim on the front edge of the cockpit. Use a stick at this height (fx on top of a book stack) to establish how far away the stick must be to let you lift out your knees comfortably. Add 10 cm for margin behind the back. This is now the length of the cockpit rim (that is if you prefer a large cockpit hole instead of a small ocean cockpit).

Measure also the distance from the wall to your heels, add the same the 10 cm. This is now the distance from the aft edge of the rim and the forward bulkhead (or foot support).

If you change the shape of the rim from the plans, make it as round as possible – any flat areas will leak at the spraydeck hem.

I prefer a large cockpit with added knee supports to a keyhole rim. Those knee supports are best added to the finished kayak – tried out sitting in the cockpit.

The deck and cockpit

Cut the deck line on the molds and reattach them in the hull. Lock them with a thin nail through the sheer strip. Tape the sheer to avoid gluing the deck to the hull prematurely.

Cut the deck line on the molds and reattach them in the hull. Lock them with a thin nail through the sheer strip. Tape the sheer to avoid gluing the deck to the hull prematurely.

Then there are two ways. I prefer to attach a cockpit dummy in particleboard on top of the molds and fit the deck strips to this. The benefits are that the deck strips automatically are aligned effectively to the rim and that you can build the rim in advance and glue it in place when the deck is finished. The other way is to strip the deck from stem to stern, cut the cockpit hole and build the rim afterward, using one of the methods below.

-

Vertical strip

This works on all kinds of decks, easily built but somewhat time consuming. Cut the cockpit hole – from the plans or your own measurements. Staple short pieces of strips (2-3”) to the deck edge round the hole. Rush on epoxy. Remove the staples, sand, laminate cloth in epoxy. Install the rim on the molds. Alternatively the strip pieces can be stapled to the edge of the cockpit hole in the deck.

-

Plywood rim

Plywood rim

For kayaks with flat or arched deck. Easily built. Build the rim in plywood pieces to 16-18 mm thickness (fx 2x9 mm or 4x4 mm) approx 15-18 mm wide. The flange can be 30-35 mm wide.

-

Laminated rim

All types of kayaks – an elegant rim. Built from sheets of veneer. Make a mold with wooden stoppers on a piece of particleboard or plywood. On this is glued several layers of veneer (mahogany, pine etc). The finished thickness should be approx 4-5 mm. Join in the front with a vertical scarph piece.

-

Steam bent rim

Steam bent rim

All kayaks. The classical way. Build a mold the same way as for a laminated rim. Use mahogany or ash, approx 2200x100x4 mm. Soak and steam the strip until limber, quickly bend it round the form and let it dry. Glue a vertical wooden mold as scarph piece in the front.

-

Recessed rim

For this rim you strip the deck and cut the cockpit hole first.

Cut a foam ring (styrofoam, polyester, urethane or similar) and glue on the underside of the deck around the hole perimeter. It can be approx 14 x 60 mm. Sand it to shape. Glue it with double-stick tape or carpentes glue.

Cut a foam ring (styrofoam, polyester, urethane or similar) and glue on the underside of the deck around the hole perimeter. It can be approx 14 x 60 mm. Sand it to shape. Glue it with double-stick tape or carpentes glue.

Laminate fiberglass and epoxy to build the necessary thickness (12-14 layers). A neat alterbnative is to start with a carbon layer, then 8-9 fiberglass layer, another carbon and on top, a fiberglass layer (recommended as a sanding layer – sanded carbon looks like the epoxy has been contanminated with soot).

Laminate fiberglass and epoxy to build the necessary thickness (12-14 layers). A neat alterbnative is to start with a carbon layer, then 8-9 fiberglass layer, another carbon and on top, a fiberglass layer (recommended as a sanding layer – sanded carbon looks like the epoxy has been contanminated with soot).

Cut the outer perimeter of the flange with a hand-held router, using the inner edge of the cockpit hole as guide (make sure the inner edge is perfectly faired). Remove the foam and sand the gutter. Sand the flange round or use a router bit.

Cut the outer perimeter of the flange with a hand-held router, using the inner edge of the cockpit hole as guide (make sure the inner edge is perfectly faired). Remove the foam and sand the gutter. Sand the flange round or use a router bit.

If you use only fiberglass, painting the rim and gutter will look nice.

Stripping the deck

Start with a center strip, carefully aligned – important for symmetry. The center strip can be mahogany, cherry or whatever you like. Next attach the sheer strip and work from there inboard towards the center strip.

Most builders staple the strip in place, lining the staple holes up symmetrically. Some build stapleless, using thermosetting glue, tape, clamps and a little ingenuity. Shape the strips individually against the rim. If needed you can staple through the rim into the strip end.

Kayaks with a rounded sheer may need a couple of narrow strips to join the hull and deck. Slice one strip into two narrow ones with the blade angled a few degrees.

Remove all staples, sand and laminate the deck as on the hull.

The flange

If you did not build the flange when attaching the rim it is time now. The flange can be made of plywood, wood strips or laminated. The simplest way is to cut two halves in 4 mm plywood and glue them on top of the rim. It should be at least 15 mm wider than the rim.

First cut the rim to the desired height. Recommended is a low rim – some 15 mm aft and 20-25 in the front. Those who sometimes paddle without a spraydeck may increase the height slightly. Draw your chosen height on the rim. Look at the line from the side. Does it look nice and smooth? A pronounced s-curve is not optimal – prone to leak at the spraydeck hem. The straighter the line the better. Adjust if needed. When you are satisfied, cut along the line.

Place a piece of plywood over the rim and trace the shape. Cut the flange parts and glue them in place. When cured round the edges with a router or sandpaper. Use thickened epoxy to make a fillet between hull and rim and rim and flange – two layers of fiberglass cloth on top. A simple and quick way is to spread the epoxy, roll out the cloth, cover with tape or thin plastic (fx a shredded plastic bag) and pull a cycle wheel inner tube over. When inflated it forces the epoxy and cloth into a nice smooth rounded fillet in one go.

Laminate two layers of fiberglass over the flange and down on the inside of the rim. Treat the underside of the deck as you did the top. Double the fiberglass around the cockpit hole. Double cloth also under the aft deck behind the cockpit (where you might climb during rescues).

Foot support

Time to decide upon foot support. If you are the only one using the kayak it is best to use a beam glued to the underdeck. To position this sit on the floor with legs straight and feet angled straight up. Measure the distance between the small of your back and the feet and add 10 cm. This is the now the distance between the aft surface of the foot support and the aft edge of the rim. Cut the beam according to the plans – shaped to the underdeck and glue it in place. Add a couple of fiberglass pieces both sides of the joint. If you are building without bulkheads and hatches, leave some 20 cm below the beam for access to the fore compartment. Otherwise make the beam part of the bulkhead. For an adjustable foot support, you can use one of the commercially available solutions or copy any one of them in wood and/or aluminum. Make them strong! In an emergency situation, you may press real hard (think surfing in shallow water, the bow hitting bottom and the only thing stopping you from sliding under the deck is these supports).

Rudder controls

Of the usual types, I prefer the VKV type (a fixed foot support with a movable yoke on top – reachable with your toes) or the surfski type of pedals (a fixed pedal with a hinged toe-controlled top part). I dislike "keepers" and sliding pegs because you cannot use the legs to power the paddle strokes without the kayak yawing – leading to leg and lower back pain. Sligthly better is old-type pedals where you at least can use the heels as a fixed point (but still limiting the use of leg muscles – think having to pedal your bike with your heels). Fixed pegs with a toe-manoevered top are OK.

The beam-yoke solution must be removable for packing, unless you have hatches – there the pegs have an advantage. But since you spend a lot more time paddling than packing and the quality aspect of the paddling is more important I still would use recommend a yoke. (Note that the yoke is attached transversally on the top of the beam – it is not the competition tiller I am referring to.)

The rudder controls must include a way to lift the rudder up on the aft deck for manoevering close to the shore or among rocks.

Join hull and deck

Put the deck back on the hull. Fix it with tape and check the fit. Sometimes the hull or deck have changed slightly from variations in temp or humidity or stressed when building the rim. Width differences of 4-5 cm you can ignore – more than that may have to be corrected with webbing around the kayak, wedges along the sheer at the hull or deck edge or temporary battens to keep the hull open. In really severe cases (f x a hull stored a long time with fiberglass on one side only) you may have to reinstall the molds when joining the two parts. In that case, you may cut holes in the molds and attach lines so you can pull the molds afterward. But normally you just glue the joint, attach some webbing and tape and leave it to cure.

Mix a batch of epoxy with a thickening agent (sanding dust, microfiber etc). Lift the deck a couple of cm and spread the epoxy mix along the edge. Put the deck down in place again  and secure with whatever is needed: staples, nylon webbing, string, tape, thin nails until the epoxy has cured. Wipe off excess epoxy immidiately. Smooth it with a finger (gloves!) on the inside.

and secure with whatever is needed: staples, nylon webbing, string, tape, thin nails until the epoxy has cured. Wipe off excess epoxy immidiately. Smooth it with a finger (gloves!) on the inside.

Sand when cured and apply 2 fiberglass tape strips along the joint – outside from stem to stern, inside as far as you can comfortably reach. No need for any acrobatics far out in the stems – the strength is needed at the midship section where the joint is stressed by the cockpit cutout and at the hatches. Furthermore, the load on the joint is approx proportional to the width of the hull – and so, negligible in the stems.

Build finish over the joint by sanding and applying epoxy until you reach the same finish as the rest of the hull.

Knee support

Knee supports are needed in large cockpits to improve the kayak contact. Sit in the kayak and use temporary plywood pieces to find the exact size and position of the knee support. A reasonabel compromise is when the pieces are easy to grab with your knees, when it is easy to slide your legs down between them and when you can work vertically with your knees between the support pieces (at least one at the time). This is a delicate balance, that takes a little time to get perfected.

Knee supports are needed in large cockpits to improve the kayak contact. Sit in the kayak and use temporary plywood pieces to find the exact size and position of the knee support. A reasonabel compromise is when the pieces are easy to grab with your knees, when it is easy to slide your legs down between them and when you can work vertically with your knees between the support pieces (at least one at the time). This is a delicate balance, that takes a little time to get perfected.

When you are satisfied, build the final supports from plywood, massive wood or laminated in carbon/fiberglass. The supports in the pic are simple but functional. Angle the underside so it supports not only the knee but also some 10 cm of the thigh for comfort. Glue them in place. A little padding (camping mat) for comfort is a nice touch.

Fixed skeg

If your kayak have a fixed skeg it is time to attach it now. Dimensions are taken from the plans. The shape is not very critical, but on some kayaks the plans depict a skeg that does not protrude below the bottom – thereby protecting it when the kayak sits on solid ground or when hitting rocks or.

If your kayak have a fixed skeg it is time to attach it now. Dimensions are taken from the plans. The shape is not very critical, but on some kayaks the plans depict a skeg that does not protrude below the bottom – thereby protecting it when the kayak sits on solid ground or when hitting rocks or.

I prefer a fairly thick skeg (12 mm plywood) that are shaped roughly to a NACA profile – rounded forward and thinned aft edge. Glue it on with thickened epoxy, taking care to get it absolutely correct positioned fore and aft. Sight along the keel or, if you are unsure, clamp a straightedge to the skeg and align this to the keel. Do not make any fillets or fiberglass reinforcements. You will not lose it in anything but a real accident – but then it can be ripped off without damaging the hull.

Rudder

Kayaks are designed for skeg (highly maneuverable) or rudder (strong tracking). Don't just slap a rudder on a skeg kayak, or a skeg on rudder kayak without a very good reason. You may be disappointed with the performance.

There are several good rudders on the market (fx SmartTrack) but on some kayaks an interesting alternative might be an integrated rudder – perhaps with a retractable blade.

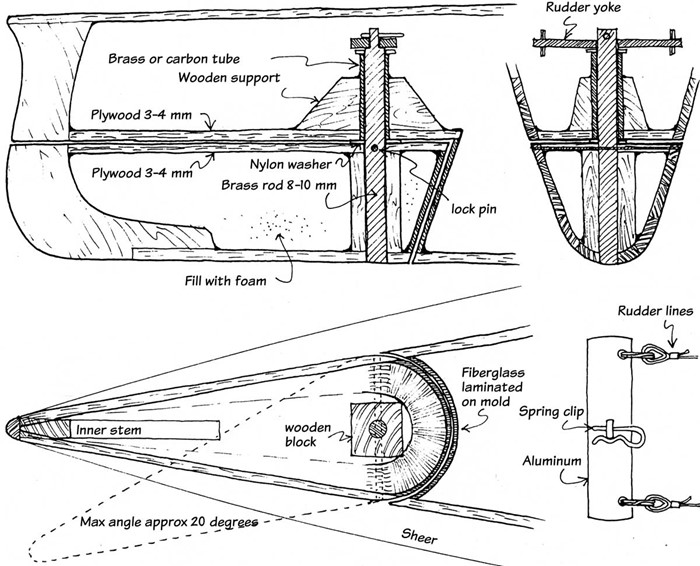

This is my original version:

Some years after this drawing was published, Rune Eurenius took the idea to a new level, by incorporating a retractable blade:

His version is described on Swedish kayak forum "Utsidan" (in Swedish only, but use fx Google Translate, if you are interested).

What's left then is the finishing, which is described after the canoe page.

-

Så här kan en enkel sittbrunnssarg byggas (bilderna är från prototypbygget av Black Pearl) Klistra skumbitar (15 eller 20 mm tjock polyester- eller uretanskum) som en form runt sittbrunnshålet. Forma innerkanten till en mjuk rundning med sandpapper. Klä ytan med maskeringstejt (för att det ska gå lätt att ta bort skumformen). Börja laminera glas- eller kolfiberväv i korta bitar – antingen ungefär 12 lager glasfiber eller kolfiber underst och näst överst med 9 lager glasfiber däremellan (det är så jag bruka…

-

När jag byggde prototypen till min Njord 2005, testade jag en för mig ny variant av sittbrunnssarg – en platsbyggd nersänkt kolfibersarg. Eftersom jag fått en hel del frågor genom åren om hur man bygger den, finns här lite bilder från processen (notera att det är ett snabbt prototypbygge, utan mycket möda lagd finish!) Men själva konstruktionen blev så bra att det är min huvudsakliga rekommendation numera – och så bra att prototypen fortfarande är min favoritkajak för långfärd. Jag har många gånger tänkt b…